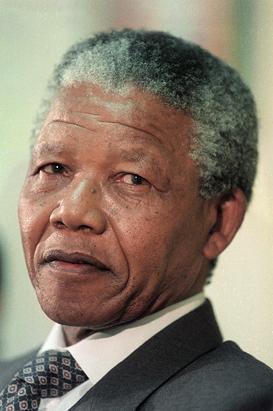

A citizen of the world. A secular saint. An icon of reconciliation. The father of a nation. A profoundly good human being. Madiba. Who can find the words to describe Nelson Mandela? Archbishop Tutu perhaps.Who doesn’t feel a sense of loss at his death? Racist bigots perhaps. I want to record my own memories in tribute  to him – very small and insignificant memories, but dear to me. As a student at university 1977 to 1982, and especially as Vice President of the University of London Union (ULU) 1979 to 1980, I was continually involved in campaigning against apartheid in South Africa.

to him – very small and insignificant memories, but dear to me. As a student at university 1977 to 1982, and especially as Vice President of the University of London Union (ULU) 1979 to 1980, I was continually involved in campaigning against apartheid in South Africa.

With my fellow activists in the Anti-Apartheid Movement, I marched, shouted, raised money and boycotted South African products. Banking at Barclays was unthinkable, as that bank was considered the most important investor in South Africa, though all the banks had investments there. As ULU Vice President (Entertainment) I booked the bands for our Rock Against Racism concerts. I organised meetings hosting Peter Hain and other leaders of the movement. We campaigned to make Nelson Mandela the Chancellor of London University, to draw attention to his incarceration on Robben Island and to put further pressure on the South African government to release him. When the Queen Mother was appointed Chancellor instead, I boycotted the degree ceremony, with other activists including my husband-to-be, who almost left his medical studies to work for Anti-Apartheid.

It’s hard to describe to my children – who have not experienced such an all-consuming political battle in their student lives – how important this was to us. Black people treated like second-class citizens, not allowed to vote, or share lavatories with whites, not considered fully human by a white government. Nelson Mandela was prepared to die in the struggle for equality in South Africa. It was the least we could do to write, march, boycott and avoid Cape grapes. His personal fortitude and courageous leadership, combined with the international boycotts and sanctions, eventually bore fruit and he was released from prison after 27 years, in early 1990. I watched the pictures live on television, Nelson hand in hand with Winnie, and I wept, with my 6 month old son on my knee. I felt that I had played my part – however miniscule – in his release, and in the forging of a new rainbow nation. It was the most significant day of my political life, proving that individuals can get together and make a difference, against seemingly impossible odds. We had sung “Free Nelson Mandela” for years, and now he was free.

Eighteen months later, heavily pregnant with my daughter, I found myself in South Africa with a group of journalists. What an extraordinary moment to be there, as the Registration of the Population Act, the final piece of apartheid legislation, was repealed. On 16 June 1991, I was in the football stadium in Soweto, on the anniversary of the 1976 student uprising, as Nelson and Winnie Mandela entered the stadium to a rapturous welcome. I shook Winnie’s hand, and narrowly missed Nelson’s but he beamed his laser smile at me. Like everyone else who has ever been in his presence, I felt honoured and humbled. We white journalists were in a tiny minority, standing awestruck on the Soweto football pitch, with every seat in the stadium filled, a sea of smiling and cheering black faces above us. Three weeks before Nelson Mandela became President of the ANC, three years before he became President of South Africa, the world so full of hope and promise – the miseries of Winnie’s trial for murder, and Jacob Zuma’s leadership failures, all in the future – on that day it felt like very heaven to be alive.

Tagged with:

Comments are closed.